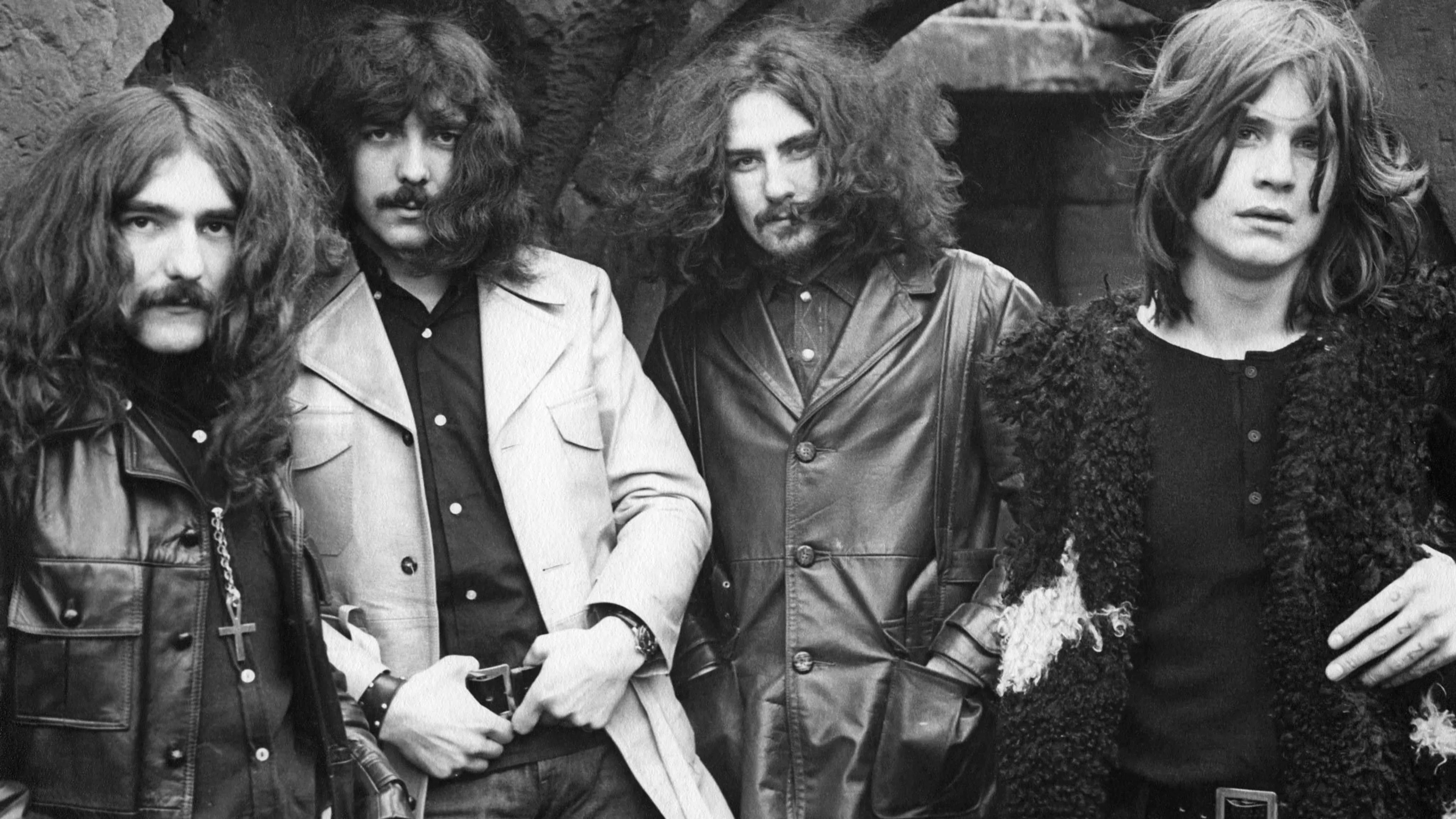

Chris’ bandleader and Tool’s old mate, Henry Rollins himself, cropped up for a trademark harshly motivational spoken word contribution to the seven minute Bottom. Tool had forged bonds with Henry while opening for the Rollins Band through 1992, perhaps finding a kindred soul in his commitment, uncompromised and famously dry humour. Typically, though, Maynard told Musique Plus – only perhaps playfully – that the legendary frontman only agreed to the part to pay back a thousands of dollars poker debt he had racked up playing with the band.

Piss-taking, fun and games aside, the record marked a moment in time that would quickly be lost forever.

Another outsider celebrity with wit drier than a peppermint fart, legendary American comedian Bill Hicks was credited as a huge influence on the band. Thanked in the liner notes and sent copies of the CD, he would reciprocate by introducing the band at Lollapalooza in Irwindale, California in August of 1993. There was tantalising talk of further, more artistic collaboration. That possibility would be snatched away by Bill’s untimely passing from pancreatic cancer in February of the following year.

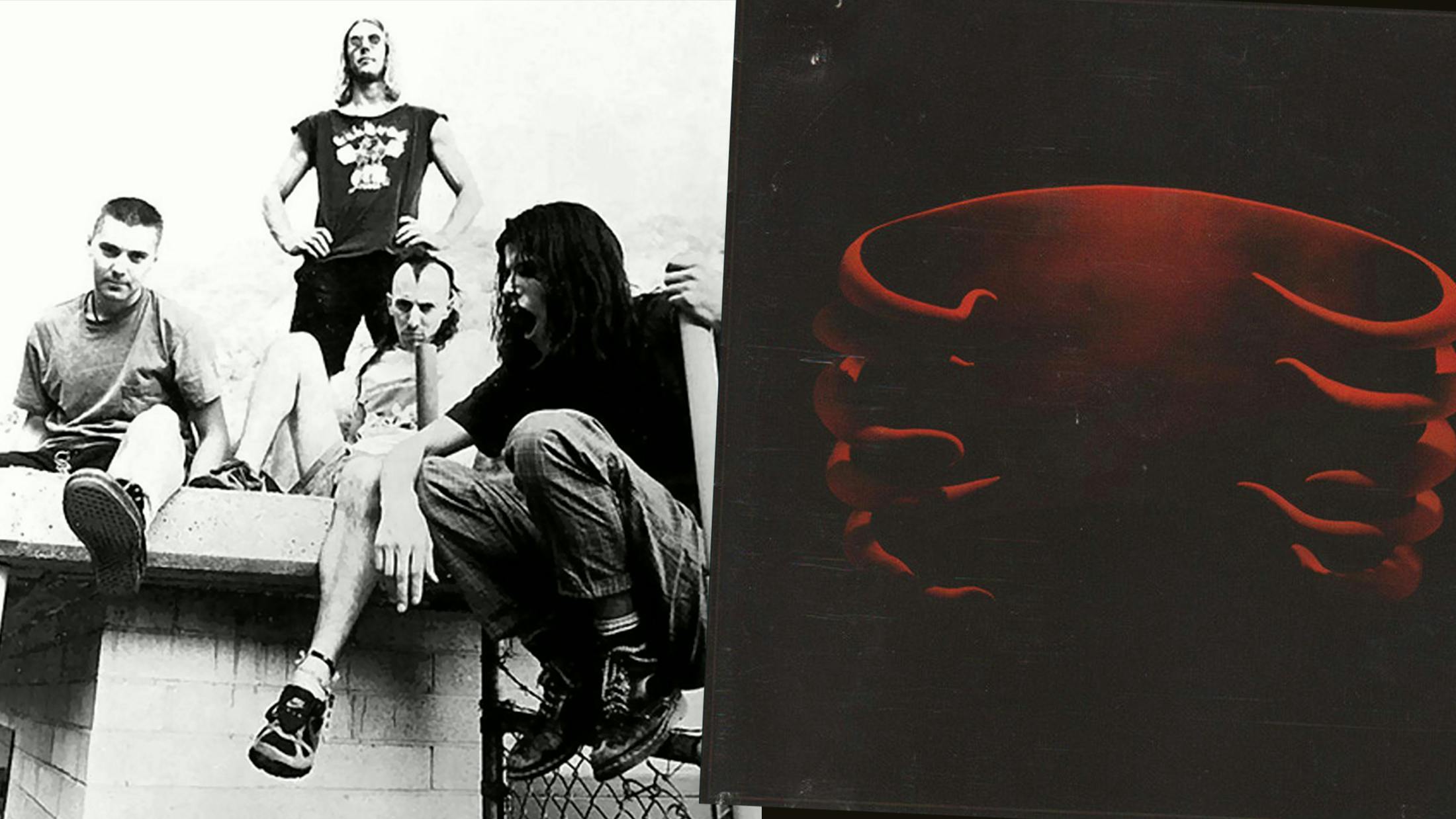

Internally, bassist Paul D’Amour had been shaken loose, too – his treble-heavy contributions betraying a desire to return to the guitar and recruit a four-string replacement. Adding another personality to the already combustible mix never felt like a realistic option for his bandmates, however, and the tension eventually led to his departure from the band and replacement by Justin Chancellor for the making of 1996 follow-up Ænima.

For a band as unapologetically exploratory as Tool, it feels strange to ponder those roads cut short and not taken. Perhaps they were necessary reroutes on the evolutionary path to becoming the world-conquering, scene-changing force we know today. Still, with the quality of these songs, and that defiant energy that many argue has gone unmatched since, you can’t help but wonder how things might’ve unfolded differently.

Over three million sales and almost three decades down the line, one thing’s for sure: as much as these four oddballs refused to be pigeonholed or placed on genre-pedestals, they triggered the tidal surge of a new breed of ‘progressive’ that would change music forever…