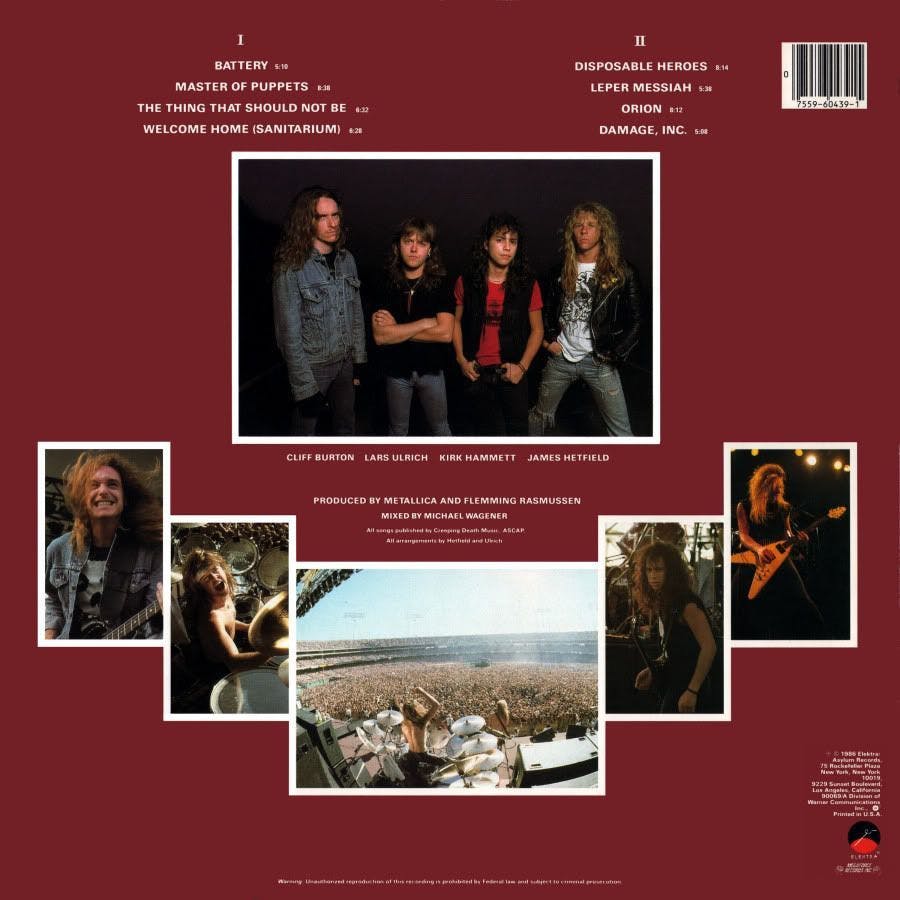

Any notion that Master Of Puppets was too much dissolved upon repeated listens and I soaked up more of the feelings that metal gave me which served me so well as a young woman: empowerment and agency. There were fields of cartoonish misogyny to navigate within metal, particularly when dealing with Los Angeles’ one-dimensional Sunset Strip drivel. Whether it was Mötley Crüe stocking all their videos with formulaic, voiceless femmes or Blackie Lawless letting us know that he viewed his dick as a saw blade, it wasn’t exactly a welcoming space for women. I shoved that nonsense aside as I got deeper into thrash while steadily feeding on the NWOBHM that initially got me to the table. At the time Metallica disavowed the value of MTV and couldn’t care less about a commercial hook, so there were no T&A videos, no lecherous leering, and certainly no pop pandering. While not all were overtly political, Metallica songs critiqued the death penalty, our failed mental-health system, organised religion, and the military industrial complex. When I listened to Disposable Heroes or Leper Messiah I felt emboldened to take on things I found frightening and comforted that there were others who preferred their metal rendered in its most pure and powerful form.

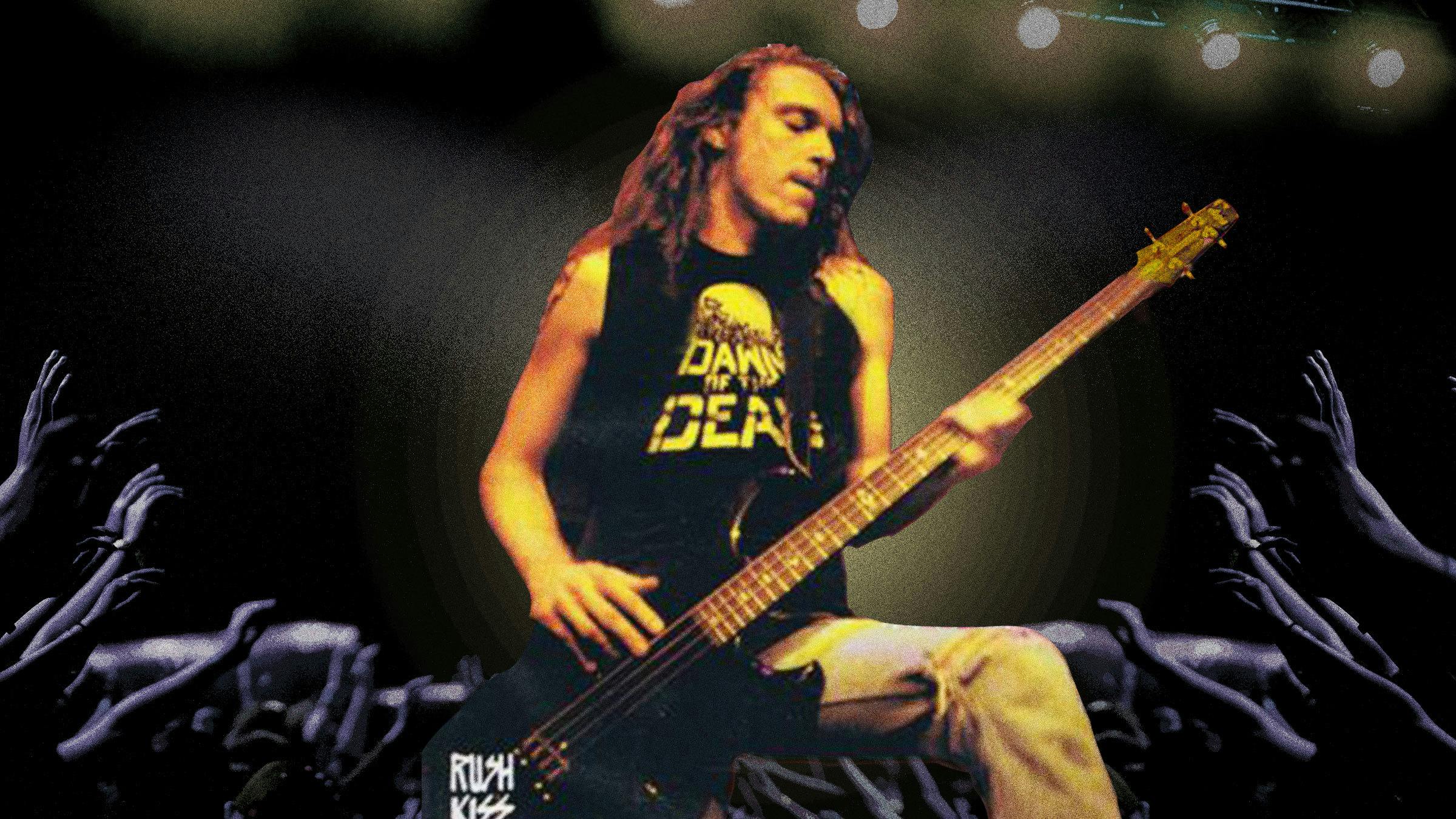

When the backbone of this sound was ripped away from us all so suddenly, the grief was visceral and charged with anger. Cliff’s bass playing wasn’t just technically impressive (though it was well-honed by his early devotion to classical music theory and diligent practice habits), it was revered for its innovative components.