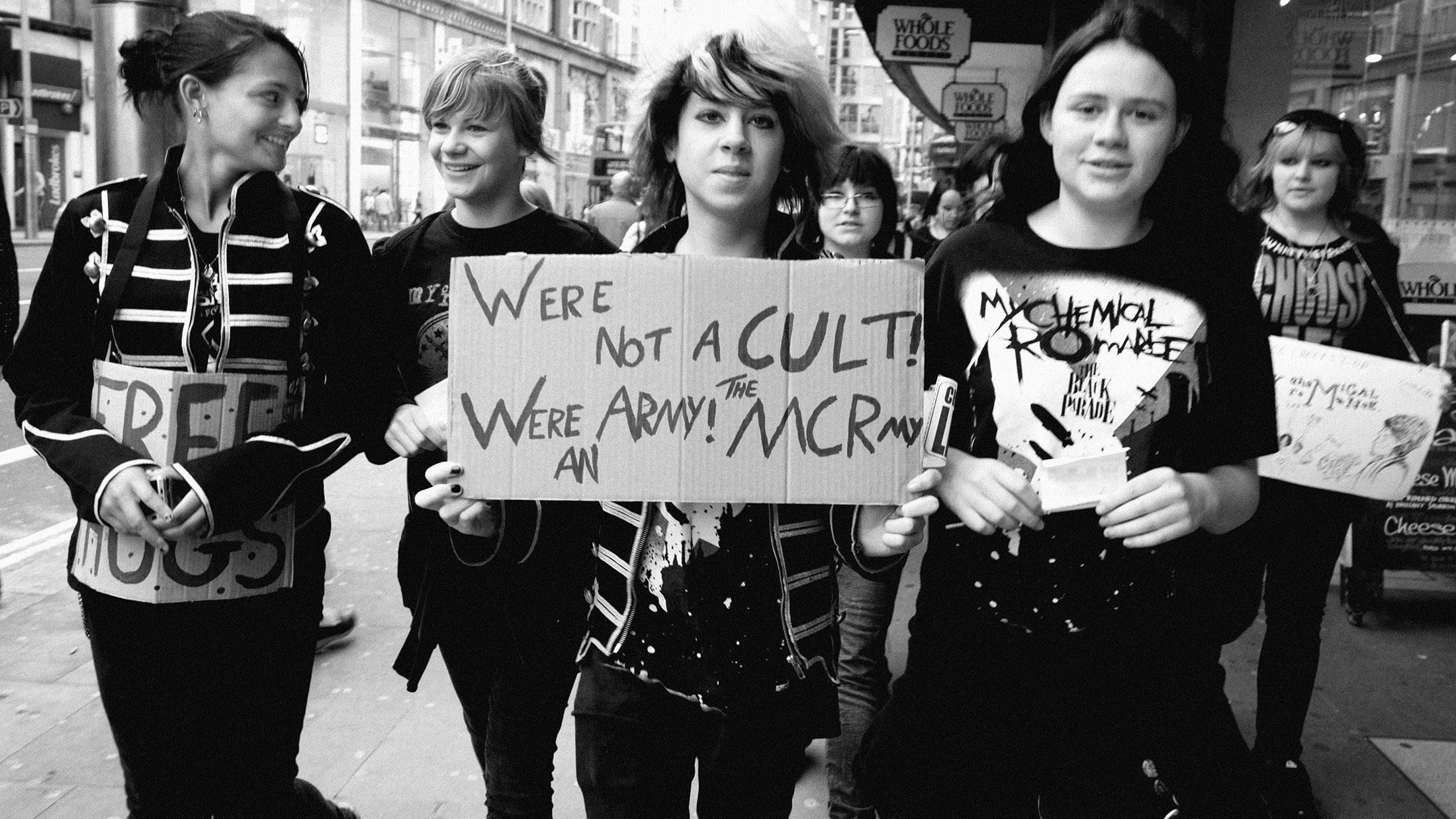

“It’s easy to place the blame on outside influences rather than admitting there might have been other things going on,” says Hayley Kennedy, now 28, who took part in the My Chemical Romance march in 2008. “Now that I’m older, I can understand a parent wanting to find a reason for such a tragedy, rather than being stuck with the unknown,” she says.

Dr Tayor says: “I’m not an expert on it, but I do get the sense that some media outlets want clear headlines. They don’t want any complexity. They just want to know, ‘The cause is this…’ and things end up oversimplified.”

It was Mental Health Awareness Week earlier this month. It provided an opportunity to reflect on just how prevalent discussions around the topic have become in the past decade. Sometimes, sadly, these conversations are sparked by the loss of someone in the public eye, such as Soundgarden’s Chris Cornell or Linkin Park’s Chester Bennington in 2017. But other times it’s musicians using their platform to share their stories, and tell those fans going through similar struggles that it’s okay for them to say they’re not okay. The media certainly has much to learn about its responsibility in this area, particularly over its obligations to young people, as some of the irresponsible, graphic coverage of the death of Swedish DJ Avicii highlighted last year.

But the complexities don’t end there. In June 2017, 10 years on from Sophie Lancaster’s murder, her boyfriend Robert Maltby spoke to The Guardian. He not only suggested that the media coverage in the aftermath of the crime was a form of victim blaming, but that the focus on him and Sophie being goths ignored deep-running socio-economic issues, including deprivation and disenfranchisement.

“Besides being patronising, the ‘goth’ thing was also an oversimplification of a much broader issue,” suggested Robert. “Life hasn’t progressed in these poor areas. There is still great dissatisfaction around. These areas are still forgotten, and forgotten people will feel like… well, it can breed nihilism. I never tried to demonise the attackers and, in many ways, they were victims.”

This invites a bigger question, and one that’s at the heart of mainstream media moral panics: who benefits from this dissemination of fear? Perhaps it’s a simple case of a blanket distrust of youth culture – we do, after all, live in a post-Brexit vote climate that has highlighted dividing lines between younger and older generations. Is it simply a case of protecting the status quo? Robert Maltby is right – there was such a blinkered focus on why he and Sophie were the victims that no-one thought to ask why teenage boys become violent perpetrators.

Look, too, at the media portrayal of millennials – people who’ve come of age in the 21st century – such as perpetuating the ludicrous myth that they’re unable to afford their own homes because they overspend on avocado on toast, rather than face up to the reality that a generation has been priced out of the housing market.

“The media has a duty to provide impartial and honest reporting rather than rehashing stereotypes,” says Sylvia Lancaster.

But what can we, as rock fans, do? Perhaps it’s best to continue doing what we have always done: listen to the music we love, support one another – and fight to change perceptions and bring about positive change.

If you are affected by any of the issues raised in this piece, please consult YoungMINDS.org.uk for more information.

Read this next: