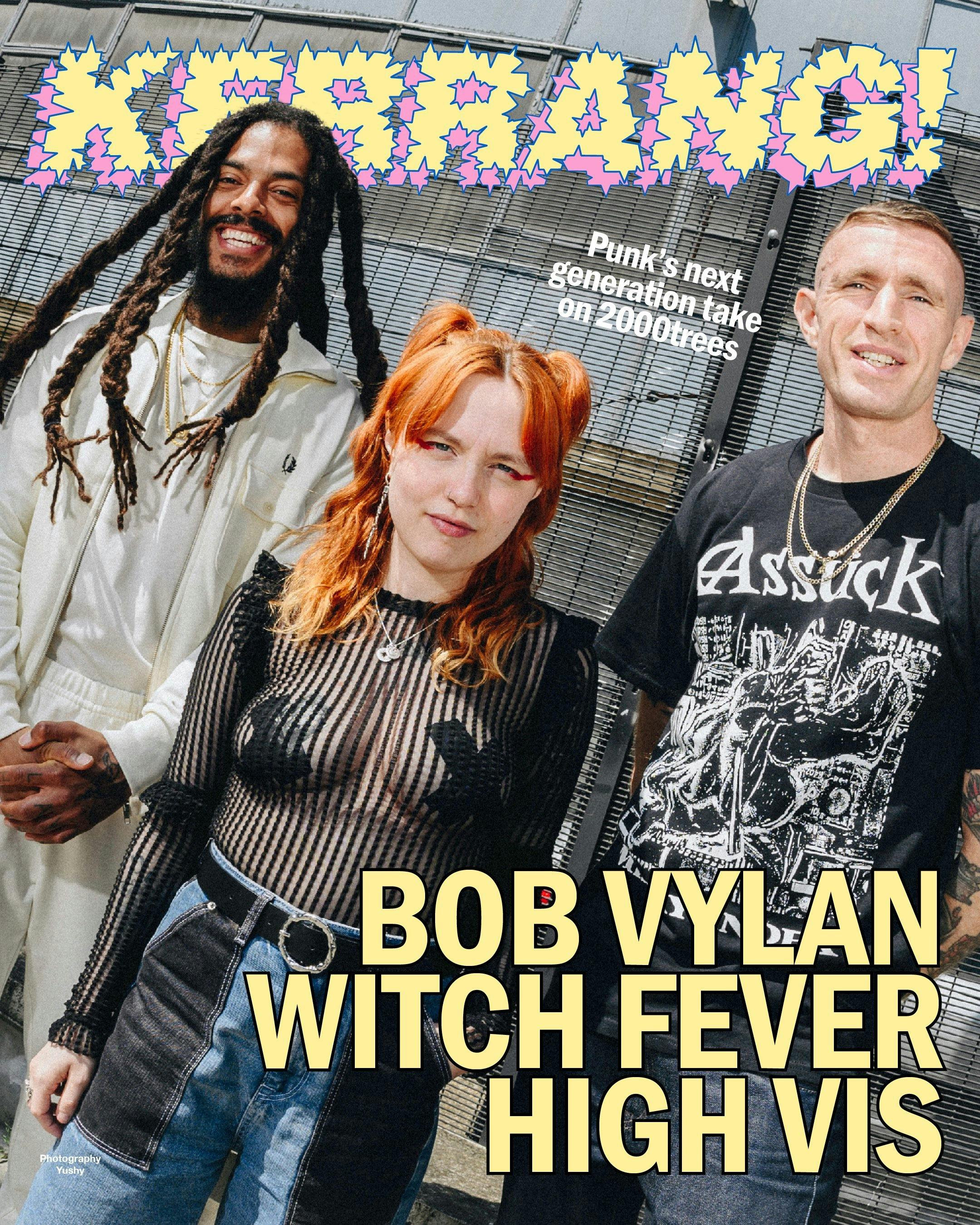

There is little doubt that what Bob Vylan, High Vis and Witch Fever are doing is important. They offer an outlet at a time when people desperately need one. Their music is vibrant and exciting, and lyrically they have found a way to scratch beneath the skin by using granular, human details to connect with listeners through anger, grief, anxiety and hope. “I've never written for anyone, I'm always just trying to make sense of stuff,” Graham says. “I think it's really important to be honest about what you know. This is such a fucking naff way of saying it, but be true to yourself, and your actual lived experience.”

For High Vis, that begins with the UK hardcore scene that spread out across the country a decade or so ago, held together by grit, determination and a lot of noise. Graham fronted the feral Dirty Money and Tremors, bands that also housed High Vis bassist Rob Moss and drummer Edward ‘Ski’ Harper, whose bedroom post-punk experiments became the basis for their melodically savvy sound. Having grown up in New Brighton, a town on the Wirral left to rot under Thatcherism, he moved to London to study at Goldsmiths, running headlong into privately-educated kids whose existences were nothing like his own. Hardcore became a haven for an outsider.

Now – more so than Bobby and Amy, whose experiences in London and Manchester have been defined at different times by cliques and othering – Graham points to a scene that has helped to prop up both High Vis and a wider network, from established labels like La Vida Es Un Mus to upstart organisations such as Fuzzbrain, a studio and community project designed to help working class kids get a foot in the door with free access to facilities.

“The hardcore scene in the UK is in quite a healthy position,” he says. “It was a scene that traditionally presented itself as revolutionary, but it was always quite conservative, I felt, when I first was getting into that stuff. Now it does feel like it's shifting in small increments, there are a lot more diverse characters in bands and it's fucking cool to see.”