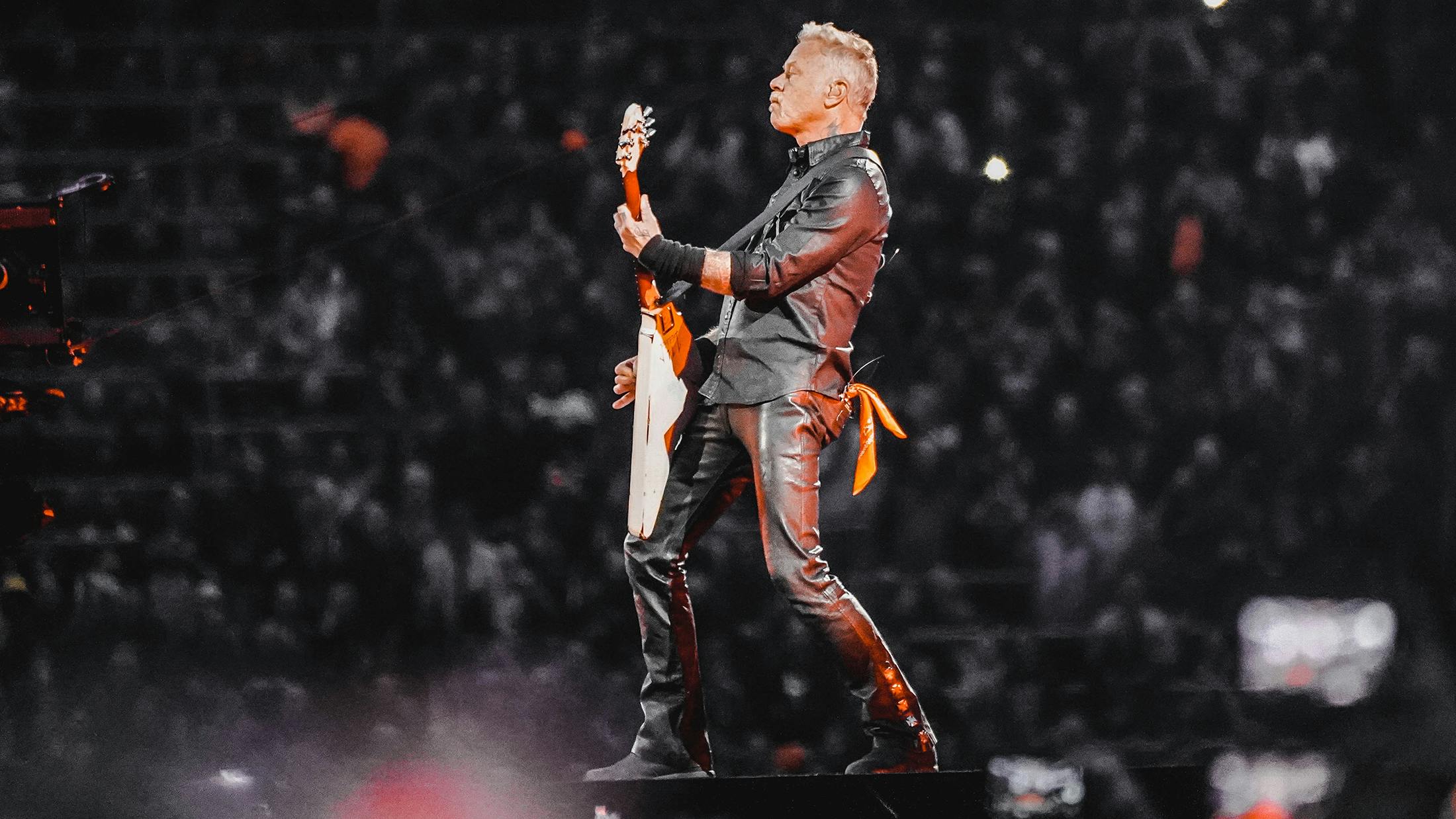

The first 72 seasons – 18 years, converted to real money – of a person’s life is the period during which one goes through the formative experiences that help define who they are. It was at this point in their own timelines that Lars Ulrich and James Hetfield came together to form Metallica in 1981. How far we are from there now. Forty-two years have passed since then, and an even four decades since they emerged to the world at large with Kill ’Em All. It’s even been longer than 72 seasons since Rob ‘new-new kid’ Trujillo joined the ranks.

And if we’re counting in seasons, Metallica are over 160 old, and into a golden autumn. The men themselves are beginning to pass their individual 60th years. As such a thing raises its own questions about what you can expect from Metallica so far into the game (a game they long ago won anyway), perhaps the most rewarding thing listening to their 11th studio album is the rough balance between the honed muscle and worldly wisdom of what’s now effectively a lifetime as the world’s biggest metal band – 32 years, if we count from The Black Album – and the high-on-testosterone-and-NWOBHM energy of the kids who made Kill ’Em All.

The first peep, Lux Æterna, may have implied this was a more openly retro-looking work than it actually is, with its openly Diamond Head-snogging riff and Papa Het’s ‘Lightning the nation’ lyrical nod, as well as harking back to Whiplash’s ‘Full speed or nothing’. Fun as that all is, it’s refreshing that this isn’t the whole story here.

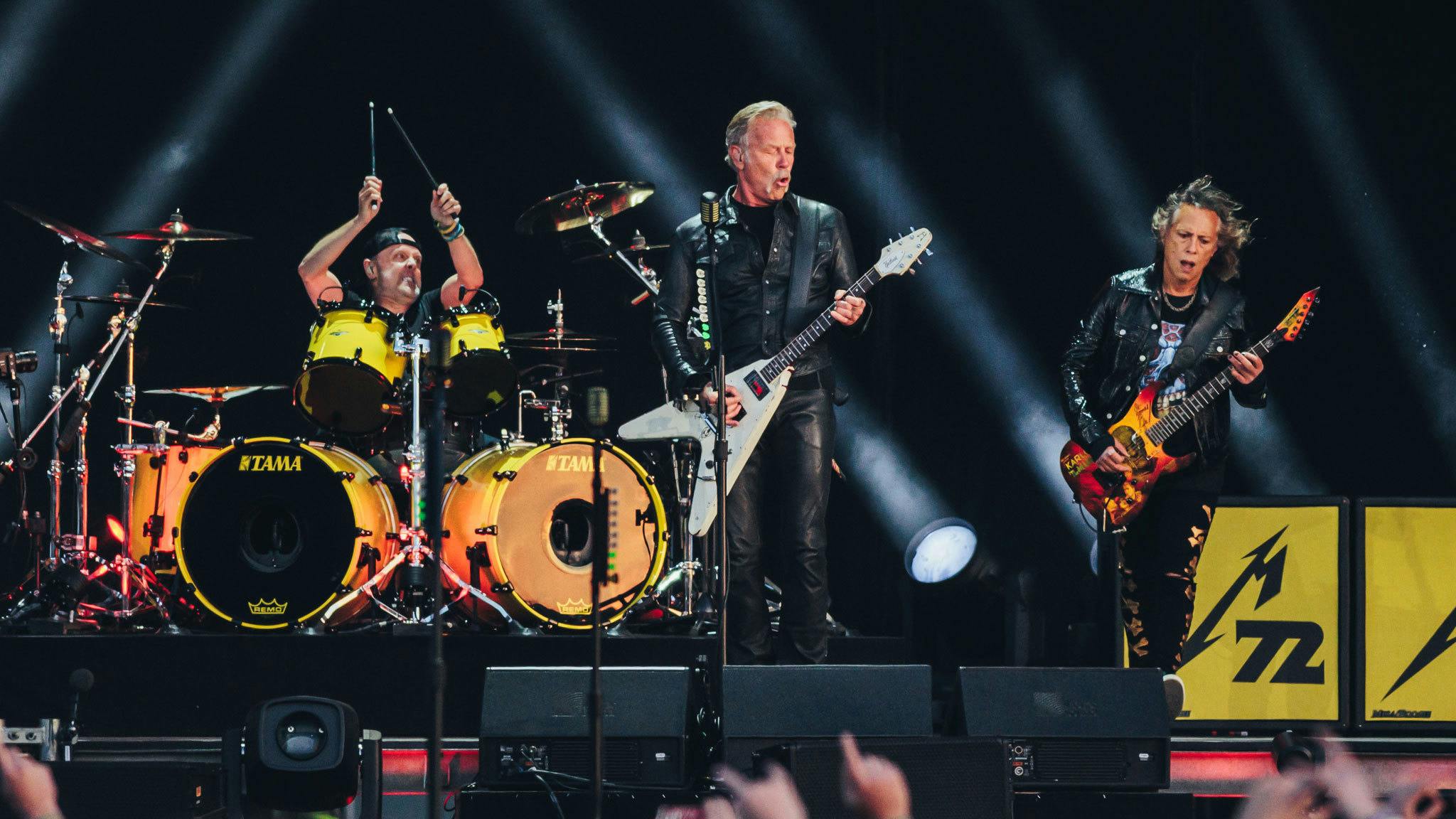

As with Hardwired… To Self-Destruct, 72 Seasons often finds the band stripped right back to a rough core. There’s a jam-room physicality in Shadows Follow’s thrusting riffs, the one-two punches of the moody Chasing Light and doomy Crown Of Barbed Wire, the thrashing mania of the opening title-track, and the NWOBHM nods of Too Far Gone?. Not that they’ve become the Ramones, not with so many riffs and stop-start stabs throwing the songs round so many corners, but the performance here is one you can hear sweating like a boxer.

There’s thrash and speed, just as there is stadium-sized, Enter Sandman-ish riffs, and the odd payment of respect to the doom of influences like Trouble, often in the same song. On the album’s home stretch, there’s shades of something approaching Rush on the intro to Room Of Mirrors, while Inamorata closes things out with the album’s most interesting, proggy melody in its fat groove, almost like Baroness. These comparisons are all fleeting and in the ear of the beholder, though: mostly what this sounds like is Metallica celebrating being Metallica.